A great, or the great, philosopher of our times — in your face, easy to understand, and an artist? Why not. Because that’s what she is.

Barbara Kruger, whose sans-serif words and sometimes images have loomed above Los Angeles since her mammoth flag mural at the opening of the Temporary Contemporary in 1990 — “Who is beyond the law? Who is bought and sold … Who dies first? Who laughs last?” — is back, big-time, across town at LACMA, in a huge, transcendent, splashy, newly opened show you have to see this spring.

And by no means not only because you need to be released from museum lockdown as the world returns to semi-normal for however long it does, though there’s that.

Mainly because Kruger’s super-sized writings and the accompanying advertising-influenced images that fill the walls of LACMA’S galleries will thrill you with the power of art and its ongoing ability to skewer the mendaciously powerful in our society the way great artists always have.

And it’s more than that in this show, expressly billed as not a retrospective, “Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You,” through July 17. It’s not there aren’t works we’ve seen before from Kruger, who made her bones in the 1980s art world with her black-and-white photographs, found images or otherwise, captioned in white-on-red Futura or Helvetica type: “Your body is a battleground,” reads one, over the face, partly printed as a negative, of a plainly beautiful model, or “We don’t need another hero” over a Norman Rockwell-ish little sister feeling big brother’s muscle.

But every time she uses an older work here, she has updated it. And the technology that makes possible big-screen video and 20-foot printed vinyl pieces smoothly applied to walls and floors allows Kruger to play around with her own words and those of others in ways that set you spinning from the moment you hit the LACMA campus.

Even as you walk up from Wilshire you are aware of a woman’s voice in speakers hidden above: “Hello, hello, hello. I love you. May I help you? Sorry,” followed by a drummer’s rim shot on the cymbal. In the Kruger-red freight elevator up to the galleries, there’s an old answering-machine message in the air: “Sorry I missed your call.” But nothing overtly political about the disembodied voices — until you step out of the elevator to see Kruger’s larger-than-life 1997 sculpture “Justice,” depicting venal lawyer Roy Cohn and the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover, both in drag, making out.

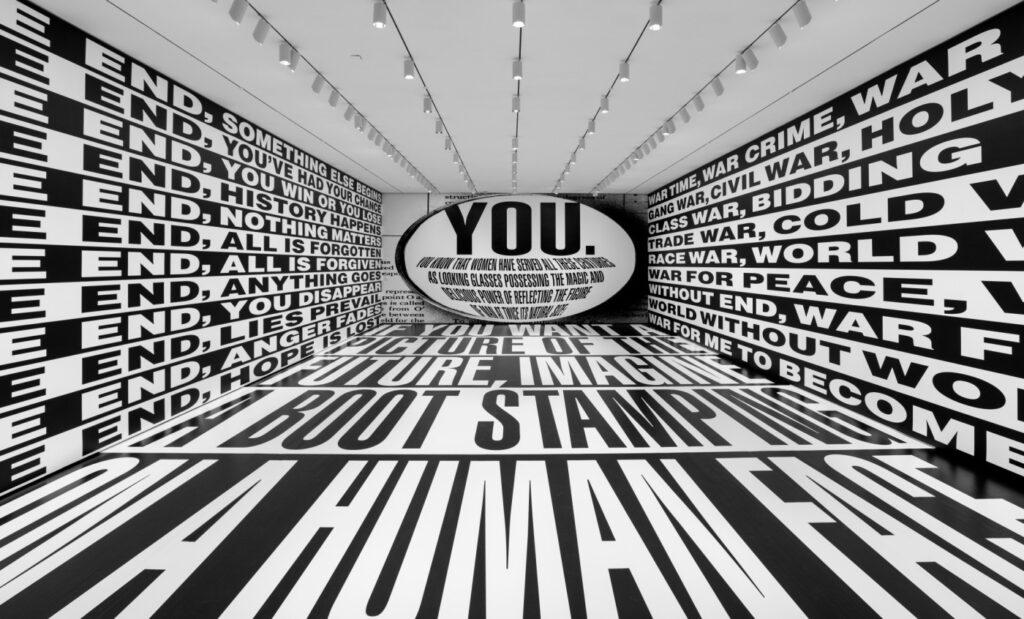

Speaking of Big Brother, around the corner is an entire room, pictured here, “Thinking of You,” with super-graphic words covering the floor and the walls in black and white, pivoting around a thought from George Orwell: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face.”

On the walls: “War time, war crime … gang war, civil war … war for peace, war without end.”

Great artists don’t perhaps need to be prescient about a Ukraine to have their fingers on the pulse. They just have to understand the human condition, where under the brutal boot of the nation-state the wars are perpetual.

In the show’s catalog, Kruger has the chance to show how an artist whose work is often displayed on the walls of a city can become part of the news, down the decades.

A centerfold photo has National Guard troops with automatic weapons crossing 1st Street in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo during the Rodney King uprisings of 1992 with her original “Who is beyond the law” mural in the background.

And she opens the catalog with a helicopter video screenshot from CNN during the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd. The copter is above Hollywood, and Kruger’s wall mural “Who buys the con?” rises above protesters being arrested by the LAPD for breaking a curfew. “7th night of protests as Trump threatens military crackdowns,” reads the crawl.

My favorite parts of this endlessly rewarding show are quieter. Funnier. Of this precise moment. “I Instagram therefore I am,” reads one of her white-on-red truisms. And after you walk past a camera that invites you to be part of a selfie broadcast on screens elsewhere in the galleries, there is an inviting bench to sit on, always welcome after a long time standing in front of pictures, in a dimly lit room. A video is about to start, which will be filled with challenging thoughts and images. But first, Kruger addresses true things about the museum-going experience: “It’s nice to be in the dark, right? You can relax a little. No brittle smiles. No air kisses. No sarcasm. Forget the stress. The worry. The petty skirmishes. Life is too short. Too short for cruelty. Close your eyes.”

As Andy Warhol, for instance, had a long career as a commercial artist before becoming an artist-artist, Kruger in her youth worked for Conde Nast and Mademoiselle designing magazines and books. To use art to bitingly show how media marketing distorts, it helps to have been on the other side of the ledger. I love the fact that when hipster product designers began stealing from her work, as skateboard brand Supreme did in the ‘90s, she never said a word. Recently, when another company stole from Supreme — a double steal — she wrote: “What a ridiculous cluster**** of totally uncool jokers. I make my work about this kind of sadly foolish farce. I’m waiting for all of them to sue me for copyright infringement.” There’s a case I’d love to cover.

Larry Wilson is on the Southern California News Group editorial board. lwilson@scng.com.