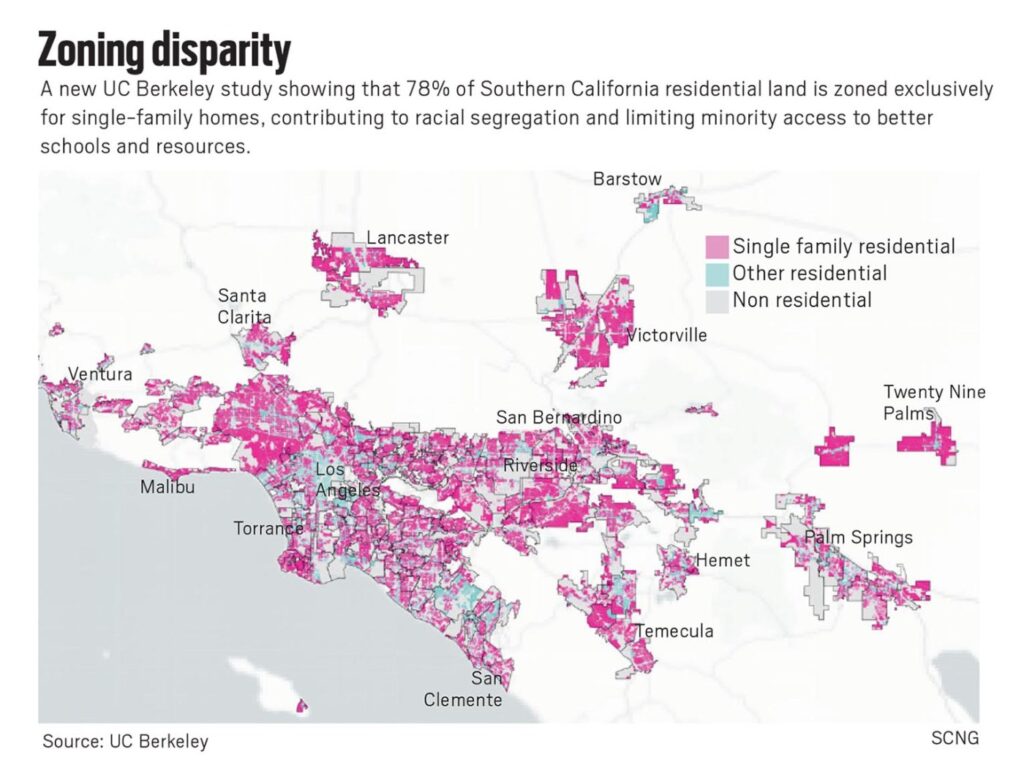

Three-quarters of Southern California’s neighborhoods are zoned exclusively for detached, single-family homes, contributing to racial segregation and limiting minority access to better schools and resources, according to a UC Berkeley study released Wednesday, March 2.

The report found that areas zoned for houses tended to be “Whiter and wealthier” than mixed-housing neighborhoods, and educational and income attainment of children raised in those neighborhoods are higher than for children from mixed-zoning areas.

The report was authored by the Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley. It’s a sequel to a 2020 study that found that 85% of residential land in the San Francisco Bay Area is zoned exclusively for single-family housing.

The study compiled land-use maps for 191 cities in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, Ventura and Imperial counties.

The study found 76% of Los Angeles County neighborhoods have single-family zoning, compared with 66% in Orange County, 79% in Riverside County and 84% in San Bernardino County.

All the zoning in six cities is limited to single-family houses: Villa Park, Bradbury, La Habra Heights, Rolling Hills, Hidden Hills and Irwindale.

“An inordinately large amount of residential land — in fact, of all land in this region — is restricted to large-lot, detached single-family homes,” co-author Stephen Menendian said Tuesday, March 1. “What this means is that apartments, condos and other housing options are simply impossible to build … and the consequences are profound.”

The percentage of single-family zoning is closely correlated with racial composition, with “significant racial changes” occurring in communities with little or no multi-family housing, the report said. Low-density zoning tends “to exclude lower-income people and people of color.”

Findings in the report show there’s a sharp drop in Latino populations and a sharp rise in White populations in communities where 80% or more of the housing is restricted to single-family homes.

Asian populations also increase in single-family neighborhoods, while Black populations showed gradual declines as the proportion of single-family zoning rises.

At least one city official questioned the conclusions of the study, saying zoning and demographic makeup “are totally separate issues.”

“A lot of people want single-family houses,” said longtime La Habra Heights City Councilmember Brian Bergman. “I don’t think it’s a fair analysis.”

The findings are based on zoning, which doesn’t always reflect the actual types of buildings in a community, Menendian said. He noted non-conforming uses either predate zoning rules or were allowed as an exception.

The study also found that neighborhoods with mixed zoning tended to have lower levels of educational and professional achievement and a “disturbing correlation” between pollution and housing.

A comparison of children raised in the 1980s showed that those from exclusive, single-family neighborhoods had higher school performance scores, higher high school and college graduation rates and tended to have higher incomes as adults, Menendian said. The level of particulate matter from auto pollution, a contributor of asthma, declines as the percentage of single-family-only zoning increases, as does the potential risk to lead exposure.

In general, zoning is used to regulate development to ensure compatible land use, as spelled out in a city’s master plan. But scholars have argued that exclusionary single-family zoning had sinister origins in the early 20th century, fostering racial segregation without mentioning race.

“The use of zoning for purposes of racial segregation persisted well into the latter half of the 20th century,” author Richard Rothstein wrote in his book, “The Color of Law,” which documented the history of racial segregation in America.

“In too many zoning decisions,” he wrote, “the circumstantial evidence of racial motivation is persuasive.”

State lawmakers have approved single-family zoning reform primarily to address the housing shortage. Past studies determined California needed to build from 1.8 million to 3.5 million new homes by 2025 to address its housing shortfall.

California and Oregon adopted laws allowing duplexes in single-family neighborhoods. Under California’s Senate Bill 9, owners can split their lots in two and even build up to four homes on the property; and under Senate Bill 10, developers can build up to 10-units on a single-family lot in transit-rich or urban infill areas if the local jurisdiction approves it.

The institute identified at least 13 Southern California cities “most in need of zoning reform” because they allow little or no multifamily housing and have failed to meet state-mandated goals for building low-income housing. Among them are Bradbury, Rolling Hills, Rolling Hills Estates, La Habra Heights, Villa Park, La Cañada Flintridge, Chino Hills and Moorpark.

Menendian said reforms could include adding multifamily and mixed-use zoning in single-family neighborhoods, loosening restrictions like setbacks and acreage minimums, and limiting the ability of neighbors to block denser housing.

Bergman, the La Habra Heights councilman, said the UC Berkeley study fails to take into consideration his town’s challenging topography. The city of 5,682 residents is built on hilly terrain with narrow, curvy roads and with no businesses, sidewalks or even sewers.

“We’re basically a bedroom community,” Bergman said. “It’s easy for someone from Berkeley to say you need this or that. But they haven’t been down here and walked the community.”

Staff writer Mike Sprague contributed to this report.