“After I killed my wife, I had twenty hours before her new body finished printing downstairs.”

Now that’s a first sentence that gets your attention. As is this: “The person sitting at the end of Kelly’s bed wore a gray, hooded cloak.”

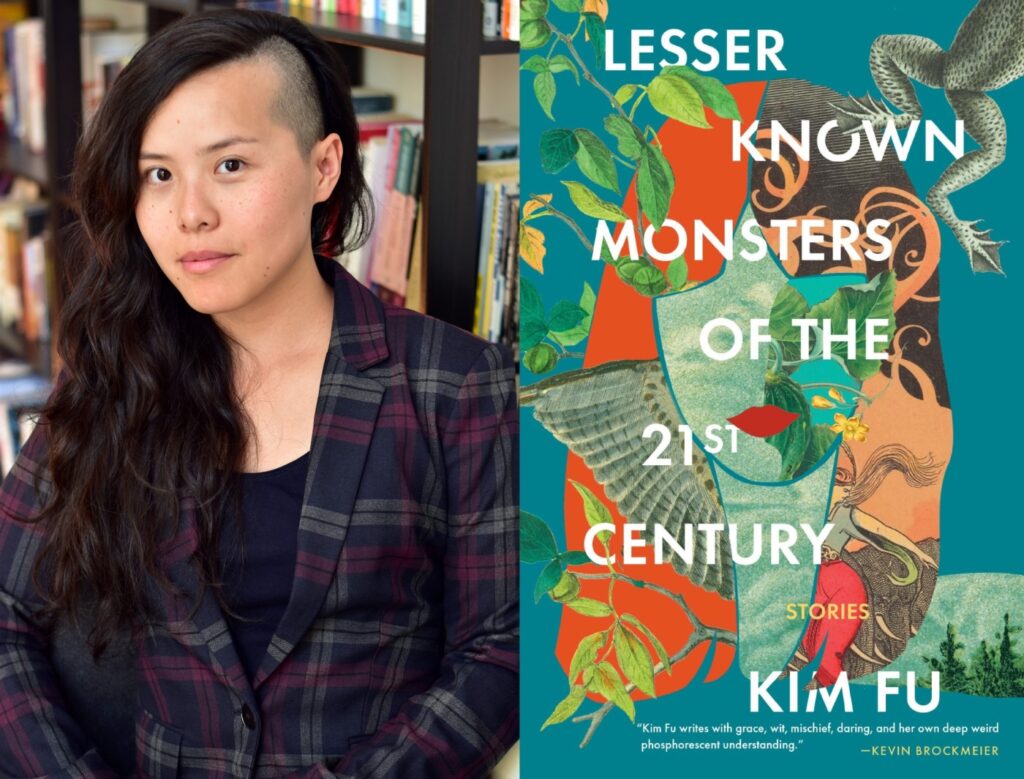

Kim Fu, a Canadian-born author of two novels and a poetry collection, has written the surreal and dazzling collection of short stories called “Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century.” It’s not just that she grabs you by the throat with those first sentences, it’s that she’s chronicling our current social ills and anxieties – loss and grief, depression, insomnia and exhaustion, technology spiraling out of control—but that she does it with riveting stories featuring unfathomable scenarios that ring true in her capable hands.

In “Twenty Hours,” a couple experiments with the ability to die and begin again. In “Time Cubes,” a new technology rewinding and fast-forwarding through time is being exploited for commercial gain before someone else takes matters into her own hands. In “Sandman,” a woman plagued by sleeplessness begins receiving special, but creepy visits from the titular figure.

And in “Do You Remember Candy,” the whole society loses its sense of taste, inspiring a woman to find a way to evoke the wondrous feelings and associations with food that we take for granted.

“I had a fear I was overpromising on strangeness,” Fu said during a recent video interview. “Other people had to tell me the book is as strange as I wanted it to be.”

It definitely is.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. What is going on in your head?

(Laughs] I used to write a lot more poetry and something of that impulse remains, the desire to literalize metaphors, to think there is a way to make emotions as big as they feel by making them into monsters or bug infestations instead of just describing them straightforwardly.

I try taking very bizarre ideas very seriously, thinking about what these characters would do in this situation

Q. Did you consciously strive to capture society’s current ills, from exhaustion and insomnia to loss of taste?

All these fears are in the air and we’re all feeling that. As a reader, I love books where the writer articulates a feeling that I had not yet put into words. I never have a real-world issue I want to write about and then come up with the monster or metaphor or image. If I set out to write something that directly reflects my worldview or tries capturing the zeitgeist, I would be paralyzed. It would be too frightening. That’s not the way I write.

Mostly, ideas come to me in the form of free-floating images or individual lines, bits and pieces where I don’t know what they are. I play with ideas and characters and images and scenes until I arrive at a place where they are saying something I want to put out in the world. It’s only in piecing things together later that those other meanings emerge.

I wrote “Do You Remember Candy” in 2019. When Covid hit I was really worried it would be painful or offensive and didn’t feel better until the story was read by people who lost their sense of taste during Covid. One woman said she liked that it took her pain seriously in a way no one else had. She felt comforted by the story. That was a huge relief.

Q. But some of the biggest chills come in stories set wholly in reality.

If a story doesn’t have a monster in it, I try having an element that functions structurally as a monster – even if it is not definitively surreal, it’s something that gives a sense of unreality and is a little destabilizing, so the story has a point of focus. The presence of a monster in a room becomes all you can think about, and I wanted there to be something like that in every story to bring up the level of intensity. It’s more important in a realistic story to find that element and home in on it.

Q. How important are first sentences in short stories?

Extremely important. When I’m reading a novel, I’m more generous and will let things build and see where it’s going. When writing a short story, you end up constructing something really tight – there’s one idea you’re hunting the entire time and you’re squeezing everything you can out of it. With so little space, you must imply a lot very quickly. So brevity is an important feature, not in terms of a particular length, but in that you must really consider every word, every sentence: if I cut this one, is the story fundamentally the same? If so, I probably should cut it.

“Twenty Hours” was inspired by the second sentence in an Elizabeth McCracken story: “One morning in the last week of May I got up, got dressed, and killed my wife.” That’s an incredible sentence. Her story is about a guy who comes out of prison after 50 years and the whole world is different. But I used that sentence as a writing prompt, asking what else could happen next and I came up with the new body printing downstairs.

Q. Did you always want to be a writer?

Even when I was small child. I have a notebook from when I was six that’s labeled Notebook 2 so there was a Notebook 1 before that, I guess.

When I was finishing high school, people told me being a writer is not realistic, this is not a career. I started my undergrad in engineering. It was the only year of my life when I didn’t write. It was miserable. I did love math and science as a pursuit of study but this was not how I wanted to spend my days. And it was so grueling there’d be no time to write. I wrote a long email to my parents and dropped engineering.

They handled it better than I expected. My dad is an engineer as is one of my sisters and the other has Ph.D. in biochemistry. My dad said, “You obviously have this strong passion so you should give it a go.”

Q. What’s in Notebook 2?

I was chronicling the day, complaining about my sisters but I was also trying to mimic the books I was reading, writing almost identical little stories, playful plagiarism. There was one about a girl who lived in caves, so I started writing one about a girl who lived in caves.

Related links

How novelist Jessamine Chan created the dystopian ‘School for Good Mothers’

How anime fuels Tochi Onyebuchi’s ‘Goliath,’ a sci-fi novel about those left behind

These 10 Noteworthy books by Southern California authors made an impact in 2021

Ryka Aoki’s novel ‘Light from Uncommon Stars’ shines upon a diverse San Gabriel Valley

Sign up for our free newsletter about books, authors, reading and more

Q. You mentioned Seattle’s gloomy weather earlier. Would this book be different if you lived in L.A.?

I’ve been in Seattle for 12 years but I lived in Montreal for five years before that and when I first moved here I was literally writing about Montreal or writing about the mood of Montreal. The moodiness of the climate took several years before working its way into my writing. I do imagine I’d write extremely different if I lived in New York or L.A. It’s not just the weather, it’s the way people interact with each other on the street and the density of people. Cities have very different energies.

Q. Do these stories reflect who you are or just your darker thoughts? In other words, which is the real you, the one whose stories I just read or the one I’m talking to now?

I’ve been thinking about that because I’m reading a couple of books right now by people I know personally – which is the truer reflection, the writing, or the person I talk to every day, who is, in general, more lighthearted and hopeful than what comes out on the keyboard at 4 a.m.?

What you say is different when you’re looking someone in the face. You don’t want to bring people down. And to a degree, it’s not useful to harp on these things in conversation especially if we’re all feeling this way.

If I’m honest, the art for me is probably the truer reflection of who I am and what I feel than I am an interview like this.